Ghost Country

Kuldīga Cemetery, 2025.

Visiting Latvia from the Next Life

They appear two mirror apparitions. On one side of the sinuous dirt driveway, a farmhouse built in the 18th century slumps toward dew-starred earth, with wounds that show its internal beams and crumbling brick. On the other side, a multigenerational home with the old shape stands firm, lamps illuminating the windows. My family sees this echo countless times as we drive across the Baltic country of Latvia in a manual Skoda. Countless farmhouses left standing alongside newer builds, grassed over like the medieval stone walls. And even eerier, the abandoned Soviet blocks,—drab concrete rectangles left empty outside villages and inside cities alike. Not all are abandoned. Some of the Soviet apartment buildings have been freshly painted in yellows and murals, but it’s only the draping of laundry lines that makes them look lived in.

We don’t see many people on our week-long trip to my grandfather’s homeland. My mom, dad, sister, and I start in the port city of Riga (Latvia’s capital), then travel to Kuldīga, Leipāja, and Ventspils. All through the trip, we reference a @knowyourlatvians video (8/25/24), in which the “True Latvian” says “Some people that watch my videos say, ‘Oo, Latvia is so nice; I’m gonna go there and make a lot of friends,’ and, you know, ugh, well [...] We’re not gonna be home.”

The rest of the Reel is clips of him panning over deserted streets, shores, and squares, repeating “There is no one here.”

“There is no one here.”

In a cemetery, he says “There are a lot of people here, but, you know, they don’t talk much.”

On our first morning in Kuldīga, my family crosses over the Venta on an ancient brick bridge, past Latvia’s widest waterfall, and into a gauzy mist that clings to the city streets, without another person to snag on. Though Kuldīga is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the cobblestone square in the center of this old city is cold, lifeless except for an illuminated fountain.

In Ventspils, we see only one active boat at the docks and pier–a small fishing vessel unloading their catch. The city square is silent except for a bell tower tolling on its edge. When we do see people, they’re often a pair: grandmothers walking children home, while two generations work abroad elsewhere in the EU.

Latvia lost a third of its population in World War II to army conscription–national, then Soviet, then German, then Soviet again–displacement, and concentration camps. For most, the mere fact that you’d survived the previous occupation marked you as a target for the next one. Nazis murdered nearly three quarters of the Jewish population; only 20 thousand Jewish Latvians survived, and many more Jews from Austria and Germany suffered in the Riga Ghetto.

The Soviet occupation that followed WWII killed and exiled even more people, with resistance fighters, academics, and politicians from Latvia’s brief first independence sent in cattlecars to gulags in Siberia. Others fled for their lives.

Maybe you’ve walked through a ghost town before, or remember the eerie empty streets at the beginning of COVID lockdowns. Neither feeling quite reaches that of traveling through a ghost country. But rather than sensing you’re surrounded by ghosts, you realize that in many ways your return makes you one.

This family trip is a haunting.

When they fled Latvia in the 1940s, my great-grandfather Alfreds chased his family across Europe, scouring message boards. My great-grandmother Vilma, Grandpa Indulis, and great-uncles Māris (Mars) and Valdis (Wally) traveled from Displaced Person camp to Displaced Person camp. Refugees, they left a paper trail on scraps, cluttered with a thousand other wilting pages: ‘We are alive, we were here, follow us to where we’re going.’ They reunited in Belgium, where Alfreds worked the coal mines, and where great-aunt Vija was born.

I live in a world where I can see every family member’s exact location through a portal in my palm; Alfreds’ physical following is almost unimaginable to me. It has a presence that punches through the digital realities I’m accustomed to. The feat of finding someone with only a few words–easily dissolved in the next rainstorm–and the recollections of strangers to guide you, feels unfathomable.

Yet their stories of survival and hunger are visceral: filling a bathtub with dark, writhing eels caught from the creek, my grandfather climbing an apple tree to pick fruit, only to witness soldiers shooting children out of the branches around him. Some stories have a visceral warmth, too: gathering shoulder-to-shoulder in the camps to sing folk songs, to hold each other and share stories and poems–to share breath, hanging in the cold air–from the home they left behind. So much of the family history I’ve heard solidified around me while we were in Latvia, making me the untethered one, the ghost visiting from another realm, from the next life.

The final ships bringing WWII refugees to the United States all required pledges and sponsorships,—people from the US who not only paid your fare, but also vouched that you’d have work upon arrival. For some, these pledges came from family or, like that for famed Riga fashion designer Olga Danoss, from people rescuing those who’d hidden them before. Most, though, received pledges through indentured servitude, sponsored by plantation or factory owners who sent contracts in languages they didn’t speak. My great grandparents were pledged to a Georgia farmer. When they passed through Ellis Island, though, they went west to join the Latvian diaspora in Michigan instead. To ensure freedom for their children and grandchildren. To be free.

I desperately want to believe this life is the next one, yet the headlines I see on a daily basis are possessed by publications found faded in library archives. Masked men without warrants are dragging people out of their homes all around the US, sending our neighbors to camps where their names mysteriously disappear off all logs. In Chicago, a secret police–masked ICE officers with no local oversight or accountability–invade homes in the night and assault people on the street. They recently kidnapped then fined a permanent resident over $100 for not carrying his papers on him.

“Show your papers.”

I see the checkpoint stamps on my great-grandparents’ papers. It’s been decades that my friends have had to carry theirs. My former Arizona roommate shared a statement from the Navajo Nation president earlier this year, which advised all tribal members carry their tribal ID whenever they leave the reservation. I remember in university, a friend from Gaza freezing when he saw turnstile gate in Seattle, how in my cruel cluelessness I made him explain to me the checkpoints that Israel enforces, has enforced for their 70-year long apartheid and genocide.

I want to believe the old world is dead, but it’s killed so many in the meantime.

Leipāja cemetery, 2025.

I read, once, that some Latvians offer more than food or drink to their ancestors at burial sites; they also offer a small washbasin, so the ghosts have a chance to bathe.

Every year in Latvia, two-to-three hundred bodies are uncovered from mass graves in the farmlands, forests, and beaches. The country is only 25 thousand square miles, not even half the size of Michigan’s landmass. For nearly a century, these bodies have suffocated in unmarked mud and dirt and sand. When I learn this count in Riga’s Museum of the Occupation of Latvia, my hands feel restless. I want to soak a washcloth with warm water and reach out to trace each lost face. I feel helpless when we find the graves of relatives in a Leipāja cemetery, and we don’t have the tools necessary to clear the ivy that has cloaked them since my grandfather’s visit in 1993.

When my mom visited the country in 2004 with her sister Miriam, she stayed with family in Kuldīga. Her relatives—her hosts—shared about their lives, surviving war and occupation, building anew for the last 13 years of independence. Everyone she spoke with has either passed on or moved abroad by the time we return as a family this October (2025).

In places–most places–Latvia is a ghost country. But there’s a culture of care for the grave sites. Remaining Latvians will spend the summer road tripping to all the cemeteries where they have relatives (or adopted sites) to rake the graves and tend to the beautiful planter boxes that adorn many of them. My mom remembers the Latvian community in Michigan tending in the same way. The Latvian government has also opened up citizenship pathways for “Descendents of Exiles.” Among the Descendents of Exiles is my mom, who was granted citizenship this year. Latvia is a country full of death, yet it’s still so full of quiet hope that it’s willing to be haunted, willing to open a portal to other realms.

Since the family my mom stayed with two decades ago isn’t here anymore, on our trip we connect to our heritage through written story and bodied presence. My mom asks our host in Kuldīga for resources on finding grave sites, and she nearly cries when we pass his elderly grandfather sitting in the downstairs kitchen because she’s so tempted to cross through the warm wooden threshold and hug him. She uses maps to find graves in multiple cities.

Mom finds translated newspaper articles about my grandpa’s cousin, who repaired Kuldīga’s city clock on St. Catherine’s Church and whose metal company produced all the antique street lamps. She then has us walk back to the church we’ve passed several times to see it anew. She finds a relative’s Letter to the Editor written during Latvia’s first independence (1918-1940) in defense of democratic process in local elections. She tells me: “See, it runs in the family.” We use a Google Drive of photos that my cousins Corey and Tiff spent hours scanning and my great-aunt Vija translated handwritten captions on to compare our visit to my grandfather’s, and to their lives before the wars.

On the coast, I’m stunned by how similar this land feels to Michigan, where my mom was raised. The low rolling hills, mixed forests and wetlands, buzzing mosquitoes, clay cliffs along long shorelines…it’s like I am for the first time hearing a sound I’ve only ever heard as an echo.

We spend a day searching for amber on the beach and another afternoon searching for mushrooms in the woods, where we find chanterelles, poor man’s licorice, and stinkhorn. Eurasian jays, white wagtails, and countless wetland birds rustle around us, alongside wild boar, red deer, and roe deer. Generations of my ancestors lived off this land, farming and foraging. A generation of resistance fighters–the Forest Brothers–fought from mossy hideouts in these forests. And on the coast, sailors.

When my mom was a kid, my grandpa Indul built a 46-foot sailboat with a handcarved wooden interior: the Thunderhead (originally called The Blue Heron). He sailed the Thunderhead all around the Great Lakes. Grandpa Indul loved to sing, especially songs in Latvian. It’s no wonder, then, that he raised five musical girls: Irisa, Miriam, Susie, Elaine, and Rose. His daughters played piano, violin, and cello, sang, and attended a Latvian school along with their public school classes. After Latvia gained their Independence in 1991 (following the Singing Revolution), Indul traveled there to visit the family farm and to give those still living there a horse. Until then, they’d been farming by hand.

Before he died (2020), Grandpa Indul was our closest connection to being Latvian, and in some ways he was our biggest barrier to it. Navigating a Latvian identity meant navigating a relationship with him.

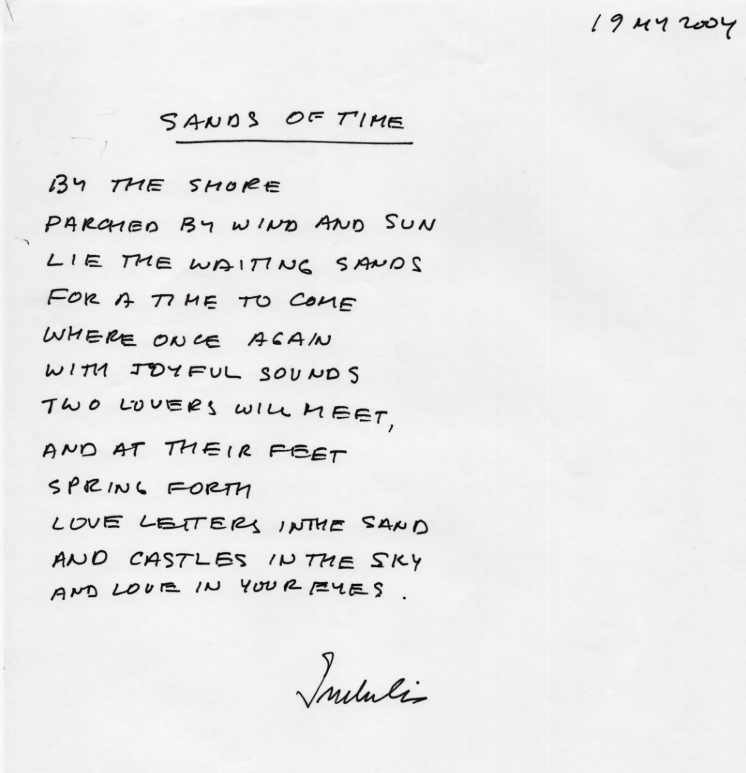

Like many refugees, traumatized people, and men raised in the 50s and 60s to be “American,” Grandpa Indul was a complicated man. He was immensely charming and creative, dashing and tall. He was an inventor with several GM patents for safety features in cars; he was a poet and a philosopher with callused hands…And he also hurt many of the people he claimed to love–not just with his sharpened words, but also with those heavy hands. For many close relatives, their capacity to see themselves as Latvian gained depth only as they lost him.

I guess that’s a common story, though: an inherited identity is always tied to those you inherit it from. All history is family history, to some degree. And family history is complicated.

Grandpa Indul’s poem, “Sands of Time,” 2004.

This family trip is a haunting…and a possession. My mom and I pass the week feeling bits of Indul living on in us as we trace the shapes and steps of lives not our own in a ghost country, where the living diaspora are ghosts alongside the dead. We catch glimmers of Indul’s demeanors and the sound of his voice in the people we encounter. We see our own faces in the features of theirs.

Each time grief crashes over our tentative joys, though, Katie uses her keychain Miks from the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia like a talisman.

Miks, a hand-felted teddy bear, is part of the museum’s interactive exhibit aimed at teaching children the heavy history of Latvia. He’s based on a real teddy bear, Jānītis, donated to the Museum by a diplomat who received it from Latvian relatives while exiled in Siberia. In each section of the exhibit, there’s a lightbox low on the wall, showing Miks through the first Russian occupation, when the Nazis took over, resisting with the partisans in the forest, being deported to a gulag, and eventually travelling the world with the diaspora. The final box we see Miks in has a handcrank to scroll through varied backgrounds with the message that through all this, Miks has survived.

Latvia has survived. Latvians have survived. We can keep surviving this world, even as it’s eating its own tail. That gives me hope. Maybe someday calling myself a Latvian won’t feel like a haunting. Maybe it will feel like a life.

Our Itinerary

10/2/25: Evening arrival in Riga. Stay in Governor’s Mansion (9 Palasta iela). Dinner at Lido’s Cafeteria.

10/3/25: Walk to the Freedom Monument, Art Nouveau District, and Museum of the Occupation of Latvia. View city from St. Paul’s Cathedral. Drive to Kuldīga, and stay between the Venta and Duke Jacob’s canal, by the Kuldīga Brick Bridge.

10/4/25: Breakfast at The Marmalade. Visit Kuldīga’s Annas kapi cemetery, the sand mines (Riežupes Smilšu Alas), and the annual Hercog Jēkobs Festival and trade fair. Walk to the waterfall (Rumba) on the Venta River while Atlantic salmon run.

10/5/25: Breakfast at Clems Maize in Kuldīga, then visit St. Catherine’s. Leave for the coast. Stop at Mežaparks on the way to Leipāja. Visit St. Anna’s and two cemeteries in Leipāja. See monument to 1919 soldiers at Northern Cemetery (Leipājas Ziemeļu Kapsēta). Sleep at Stella in Ziemupe.

10/6/25: Beach walk and polar plunge in the Baltic Sea. Afternoon in Ventspils at the city square, pier, and restaurant Meisons DarbaLaiks. Return to Ziemupe.

10/7/25: Return to Riga, stopping in Saldus for coffee and to see the bronze statues on Sv. Jāņa’s steps. River cruise in Riga, then visit the House of the Blackheads, the Riga Market, Baltu Rotas, and the restaurant Gōngu. Sleep at Forest Edge near the airport.

10/8/25: Morning departure from Riga.